Beadwork has a way of pulling people in — the steady rhythm of thread, the tiny click as beads slide into place, and the slow revelation of a pattern. This article offers a practical and creative tour for anyone curious about bead weaving and loom work, blending basics, technique, and design in one place. Whether you pick it up for calm, craft markets, or to make gifts, you’ll find clear steps and real-world tips to start with confidence.

What bead weaving is and why it matters

Bead weaving is the practice of joining beads together using thread, needle, or wire to create flat or sculptural pieces. It can be as simple as a narrow bracelet or as complex as beaded tapestries and wearable art meant for galleries. The craft sits at the crossroads of textile technique, jewelry design, and miniature sculpture, offering wide room for personal expression.

Historically, beadwork appears in cultures around the globe, from Native American peyote stitch to West African bead strings, and these traditions inform modern approaches. Today, makers combine traditional stitches with contemporary materials and tools, so the field feels both grounded and experimental. Learning bead weaving opens doors to new patterns, trade communities, and the satisfaction of making something tactile and durable.

On a practical level, bead weaving trains patience, hand-eye coordination, and planning skills. It also scales well — you can work for a few minutes at a bus stop or spend an afternoon on a large panel. Those small wins add up: two hours of focused beadwork often produces visible progress that feels rewarding.

Overview of loom work and how it differs

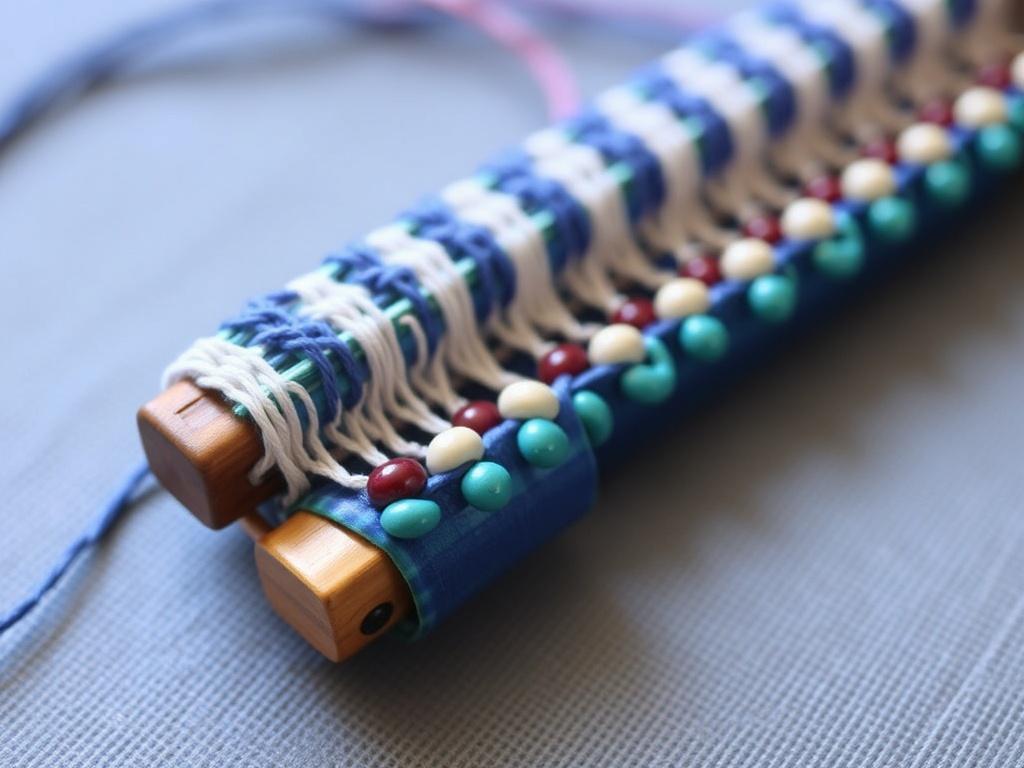

Loom work is one branch of bead weaving where beads are strung across warp threads on a frame or handheld loom, producing consistent rows and flat, geometric patterns. Unlike off-loom stitches that build bead-by-bead with a needle, loom pieces are typically created width-wise as rows, which makes them faster for repeating designs. Loom work excels at bands, wide bracelets, belts, and panels used for insets in garments.

The loom imposes a grid, and that grid is both a limitation and an asset: it simplifies pattern translation, but it also constrains bead placement to a regimented matrix. That regularity allows precise offsets and colorwork akin to pixel art, which is why many designers use looms for patterned projects. If you enjoy designing motifs and want to reproduce them exactly, a loom offers reliable symmetry and repeatability.

Functionally, beginners might find loom work easier to visualize since beads align in straight rows, while off-loom stitches require learning stitch geometry. Both techniques share tools and materials and often complement each other in mixed-media projects. Most makers learn a few stitches off-loom then explore loom work to diversify their skillset.

Tools you really need

Starting with the right tools keeps frustration low and results high. At a minimum, you need quality beads, a beading needle, appropriate thread, scissors, and a flat work surface. Each of these elements affects tension, durability, and the overall look of your finished piece.

Beading needles are very thin and flexible; they slip through tiny bead holes and make complex stitches possible. Threads come in various weights and materials; nylon threads like Nymo and monofilament options each behave differently, so testing is essential. Good scissors and a bead mat prevent beads from scattering and protect small pieces, which makes the craft far more pleasant.

If you plan to do loom work, a small loom — either a warping board style, a rigid heddle, or a compact bead loom — is worth the investment. Largely inexpensive looms allow you to experiment with different widths and warp densities. I recommend buying a beginner loom that accepts removable warps so you can practice without committing to a large frame.

Materials: beads, thread, and core choices

Seed beads are the backbone of bead weaving; size designations like 11/0, 8/0, and 15/0 indicate bead diameter and hole size. A larger number like 11/0 means the bead is smaller than an 8/0; the choice depends on the level of detail you want and the thickness of your thread. Glass seed beads are common for their uniformity, shine, and color variety, while metal, ceramic, and crystal beads serve decorative roles.

Thread selection influences both flexibility and longevity. For delicate pieces, finer threads let beads sit closer; for robust jewelry, heavier threads or coated braided lines add strength. Specialty threads such as FireLine or WildFire offer high tensile strength and abrasion resistance, often recommended for bracelets that see regular wear.

Other materials to consider include thread conditioners to reduce tangling, beading awls to coax stubborn threads, and beading trays to organize colors. Storage solutions — small containers or compartment boxes — keep projects tidy and save time. Choosing a few reliable brands and tools early simplifies the learning curve.

Types of bead looms and their pros and cons

Loom choice affects portability, potential project size, and the learning process. There are three common categories: fixed-frame looms, small portable looms, and bead boards or DIY looms. Each type suits different makers, travel habits, and storage constraints.

Fixed-frame looms are stable and handle larger projects comfortably; they often feature adjustable heddles and tension controls. That stability helps when working with many warps or when aiming for perfectly even tension across a wide piece. The downside is size — they can be bulky and less convenient to store.

Portable looms, like small wooden bead looms or compact UFO-style looms, are lightweight and ideal for bracelets and small panels. They let you bead on the go and typically cost less, making them great for beginners. However, their smaller working area limits project scale and may require more frequent re-warping for long pieces.

DIY and alternative loom approaches

You can make a basic loom from cardboard, clothespins, or a stiff piece of wood, which is perfect for testing patterns without investing in equipment. DIY looms teach you the mechanics of warp tension and spacing so you understand how professional looms function. Simple looms also make excellent classroom tools or introductions for kids.

Another approach uses temporary frames like bead boards or even tape on a table to hold warps in place while you work. For some designers, integrating a rigid heddle or repurposed frames creates unique textures. These alternative looms require more hands-on adjustments but reward inventiveness.

My first loom was a DIY cardboard frame and it taught me two vital lessons: tension matters more than you think, and easy repairs beat perfect materials when you’re learning. That early hiccup saved money and helped me appreciate how warp spacing influences pattern clarity.

Basic stitches you should learn first

Start with a small set of stitches that appear across many projects: square stitch, peyote stitch, brick stitch, and loom stitch. These stitches cover a wide range of applications and build a foundation for more complex techniques. Each stitch also teaches different ways beads can be joined, which is the essence of bead weaving.

Square stitch mimics loom rows while working off-loom, making it a useful bridge between techniques. Peyote stitch is versatile for flat, tubular, or circular pieces and yields a slightly textured surface. Brick stitch excels for sharp edges and stair-step shapes, often used for motifs and fringe.

Loom stitch is essentially the method you use while working on a loom: beads are threaded across the warp and secured by passing the weft thread under the warp and through the beads. Once you understand that logic, you can translate loom patterns into off-loom equivalents and vice versa. Learning these stitches makes pattern reading and design much easier.

Step-by-step: starting a simple off-loom square stitch

Prepare a comfortable workspace with good light and a bead mat to prevent rolling. Thread a needle with about an arm’s length of thread, and pick a bead size — 11/0 is an accessible starting point. Tie a small stop bead near the end of the thread to keep beads from sliding off while you work.

String your first row of beads in the desired width, then form a loop by passing your needle back through the first bead to secure the row. To add the next row, pick up one bead, pass the needle under the thread bridge between two beads in the row below, and then back up through the new bead. Repeat across the row, maintaining even thread tension, and add as many rows as needed for your sample or project.

Finish by weaving the thread back through several beads and knotting it discreetly, then trim the excess. Practicing this stitch builds rhythm and helps you understand how bead placement works in a grid. Square stitch is a reliable way to make banded pieces like bracelets and watchbands.

Design basics: reading and creating patterns

Patterns are often presented in grids where each square corresponds to a bead; loom designs map directly to these grids. When reading a pattern, note whether the designer used color codes, symbols, or numerical counts. Translating pattern charts to bead colors and row counts keeps your work organized and reduces mistakes.

Creating your own pattern starts with a simple grid sketch or using bead-design software, many of which are inexpensive or free. Begin with a motif no more than 10-20 beads wide to avoid overwhelm, and consider repeating it for a banded effect. Test color combinations on a small swatch to check contrasts and readability at a tiny scale.

Grids are forgiving: if a color reads muddy or a motif looks off, you can adjust the draft and rework a small section. Many designers carry tiny swatch samples or create a color card for their palette to ensure consistent choices across projects. Over time you’ll develop an eye for how bead sizes and finishes affect perceived color and pattern sharpness.

Color and texture strategies

Color choice is threefold: hue, value, and saturation. Value — how light or dark a color is — often matters more than hue for legibility in beadwork, so prioritize strong contrasts between foreground and background. Metallics and transparent beads respond differently to light and can introduce unintended shimmer or depth; use them deliberately for highlights or accents.

Texture comes from bead finish and shape; matte beads mute reflections while glossy beads sparkle. Mixing finishes can create dimensional effects without adding complexity to the pattern. For instance, a matte background with glossy beads for the motif can make the motif pop under indoor lighting.

Try limiting your first projects to a palette of two to four colors and one accent finish. This restraint simplifies decisions and makes clear design choices. Once you understand how beads behave, you can expand palettes without losing control.

Project walkthrough: making a simple loom bracelet

This sample project demonstrates core loom skills: warping, bead placement, tension management, and finishing. It’s a manageable first piece that yields a wearable result and helps you practice pattern following. Gather your loom, warp thread, beading thread, beads, and a clasp before starting.

Step 1: Warp the loom by securing the warp thread across the loom at even intervals for your desired width. Tension these threads so they are taut but not overstretched — they should give slightly under a finger’s pressure. The number of warps depends on the bead size and whether you want one bead per warp space or alternating placements.

Step 2: Follow your pattern row by row. Slide the beads into place on your beading needle and lay them into the gaps between warps. Pass the needle under the warps, pull the thread back through each bead, and secure it by passing the needle back under the warp threads, trapping each bead in the correct grid position. Repeat this process until you reach the bracelet’s length.

Finishing the loom piece and adding hardware

To remove the piece from the loom, gently tie off each end by looping the warp threads into secure knots or by weaving them back into the beadwork for a cleaner finish. Attach end caps, clamshells, or foldover clamps to provide a professional closure for the bracelet. Adding a jump ring and lobster clasp completes the hardware and makes the bracelet wearable immediately.

If you prefer a softer finish, sew a backing of leather or felt to protect the beadwork and cover knots. That backing also improves longevity and comfort while wearing. In my early market days, customers appreciated the clean edges and felt backing because it prevented snagging on clothing.

Translating loom patterns to off-loom stitches

You can recreate loom patterns using square stitch off-loom, which mirrors the grid layout bead-for-bead. This flexibility is useful when you need the look of a loom piece but prefer a handmade stretch or shaping that looms don’t easily provide. Conversion involves reading the loom chart and reproducing each row with a square stitch sequence.

For more organic shaping, peyote stitch can approximate patterns but will shift bead alignment slightly due to its offset geometry. Brick stitch yields sharp triangular edges and works well for pointed motifs inspired by loom designs. Understanding these equivalencies lets you mix approaches within a single piece for emphasis or structural reasons.

Many designers use a hybrid workflow: produce a central panel on the loom, then use off-loom stitches to add edges, fringe, or three-dimensional elements. That combination creates visual contrast and initially was how I learned to break monotony in wider pieces. It keeps designs dynamic and shows technical breadth to customers and peers.

Troubleshooting common problems

Tension issues are the most common stumbling block for beginners: loose beads make gaps and uneven rows, while overly tight tension can warp the piece. If your rows look wavy, re-evaluate warp tension and the tightness of each pass with the thread. A consistent gentle pull — firm but not bone-tight — yields a flat, even surface.

Thread breakage often results from using a thread that’s too thin or from abrasion at beads with rough holes. Use strong, smooth thread for long projects and consider pre-conditioning threads to reduce fray. When working with metallic or large-hole beads, test for sharp edges and file them if necessary; a few minutes of prep prevents weeks of frustration.

If your pattern doesn’t align, check your bead counts and ensure you didn’t misread a chart row. Marking rows on a paper chart or using a digital pattern app helps prevent lost places. When a mistake appears far back, it’s often better to undo a few rows and correct than to try to force a patch — the repaired section looks neater and holds better.

Finishing techniques that make a piece last

Secure finishing is essential for jewelry that sees regular wear. After tying off threads, weave the ends back through several beads before trimming, then apply a tiny drop of specialized jewelry glue on internal knots for extra security. Avoid gluing visible areas; a dab on hidden knots prevents unraveling without altering the look.

Crimping and attaching high-quality hardware, such as stainless steel or plated brass, reduces breakage at stress points like clasps. For bracelets, fold-over clamps and end beads distribute tension evenly and make the item easier to wear. A well-executed finish is what separates hobby projects from items you’d sell at craft fairs.

Maintenance also extends life: advise wearers to avoid chemicals like chlorine or perfumes, and provide a small cloth for occasional wiping. Store beadwork flat to prevent warping, and keep it away from sharp objects that could snag thread. Simple care instructions increase customer satisfaction and lower returns.

How to price your beadwork for sale

Pricing should reflect materials, labor, overhead, and desired profit. A pragmatic rule is to calculate material costs, multiply labor time by an hourly rate that values your skill, and add a margin for overheads like tools, shipping, and marketplace fees. This yields a baseline, which you can adjust for market positioning and brand identity.

Time-intensive techniques like fine peyote or intricate loom patterns deserve higher labor rates, and limited-edition designs can command premium prices. Track your time accurately for several projects to find realistic averages; novices often underestimate how long finishing and tidying take. Adjust pricing as you become faster and more efficient, but never undervalue expertise.

Consider also intangible value: design originality, local sourcing, and handcrafted authenticity can justify higher prices in the right markets. At one craft fair, a thoughtfully packaged bracelet with a story card about technique and materials consistently sold faster than cheaper but generic items. Presentation matters.

Resources: books, software, and communities

Books remain valuable for structured learning — classics cover foundational stitches, pattern design, and historical context. Look for titles that include detailed stitch diagrams and step-by-step photos. Libraries and secondhand bookshops often carry excellent manuals at modest prices.

Design software, from simple grid editors to dedicated bead-pattern programs, helps you visualize charts and export color palettes. Some apps simulate bead finishes and lighting so you can preview how metallics or transparent beads will appear. Using a layout tool shortens the sampling phase and reduces wasted materials.

Community is where many beaders grow fastest. Local guilds, online forums, and social platforms host pattern swaps, critiques, and trade groups where you can sell or trade beads. Joining a community provides real-time feedback and encourages creative risk-taking that solitary practice rarely achieves.

- Recommended reads: stitch guides and pattern compendiums

- Software suggestions: bead grid apps and general design tools

- Communities: local craft guilds, Instagram hashtags, Ravelry-like bead forums

Teaching and learning paths

Start with short workshops or community classes to get hands-on instruction and immediate troubleshooting. In-person teachers can correct posture, needle handling, and tension — small adjustments that save hours of frustration. Many community colleges, art centers, and bead stores offer evening classes tailored to beginners.

Online courses and video tutorials provide flexibility and the ability to rewatch difficult steps. When choosing an online class, prioritize teachers who show close-up views, explain troubleshooting, and include downloadable patterns. Peer reviews and course previews help you avoid badly produced lessons.

If you plan to teach, begin with a narrow focus: a single stitch and a small project. Students succeed when they finish something wearable and sense progress. My first teaching stint focused on a one-hour bracelet using square stitch, and watching students’ faces when they completed it was more rewarding than any sales moment.

Expanding skillsets: advanced techniques and mixed media

Once you have the basics, explore sculptural beadwork, bead embroidery on fabric, or integrating metal components and gemstones. Techniques like netting, herringbone, and three-dimensional peyote open possibilities for necklaces, crowns, and small sculptures. Experimentation often leads to signature styles that distinguish your work in a crowded market.

Mixed media projects combine beads with leather, metal blanks, weaving, or fiber elements, creating pieces with tactile contrast. Combining a loom panel with leather backing, metal rivets, or a resin bezel makes striking statement pieces. Those cross-disciplinary methods also attract collaborations with designers working in fashion, product, and interior design.

Advanced makers often develop custom colorways and order specialty beads for collections, which transforms craft into small-scale manufacturing. A small-level production approach — repeatable patterns, consistent materials sourcing, and quality control — scales handwork without sacrificing craftsmanship. That path requires process thinking in addition to artistic skill.

Safety and ergonomics

Beading is sedentary and precise work, so pay attention to posture, lighting, and eye care. Use a magnifier for prolonged detail sessions and take regular breaks to stretch hands, shoulders, and neck. Proper lighting reduces eye strain and prevents mistakes that occur when colors look off in poor light.

Maintain a tidy workspace to avoid hazards like lost needles and scattered beads that can cause trips or inadvertent ingestion by children or pets. Keep small parts in labeled containers and store needles in magnetized dishes or dedicated cases. These small safety habits protect you and preserve the longevity of your tools.

When working with chemical finishes or adhesives, ensure good ventilation and follow manufacturer guidelines. Glues and solvents can irritate skin and respiratory systems if misused. Gloves and masks are rarely needed for routine beadwork, but they’re sensible when applying strong adhesives in enclosed spaces.

Real-world examples and a personal project story

A few years ago I designed a commission piece that combined loom panels with hand-stitched fringe for a community theater costume. The director wanted a period look with an updated palette, and the project demanded both speed and durability. Loom sections provided the patterned base, while off-loom beadwork created flexible, movement-ready fringe that held up under stage lights.

Working on that commission taught practical lessons: use a robust core thread for stage wear, plan panels to accommodate costume seams, and test colors under performance lighting. The piece endured many shows and several washes, plus it photographed well from the audience. That job led to further commissions because the costume team valued a maker who understood both aesthetics and performance constraints.

Smaller success stories happen at craft fairs too: a simple loom bracelet with a unique color mix sold twice as fast as other items because the palette matched local tastes. Observing buyer reactions helped me refine color offerings and finalize a few reliable best-sellers. These incremental lessons build sustainable creative businesses.

Continuing your practice

Make tiny experiments part of your routine: a 15-minute daily stitch builds muscle memory and prevents creative burnout. Keep a small sketchbook or digital file for ideas, color swatches, and notes about thread behavior or bead sources. Over time those snippets become a personal reference that speeds project planning and reduces redundant trial runs.

Attend shows, swap meets, and online markets to discover new beads and techniques. Handling materials in person reveals qualities that photos never convey. Networking with other makers exposes you to new workflows and often results in collaborative projects that expand your audience.

Set a few reachable goals: learn a new stitch every month, design a small collection each season, or teach a friend. Goals keep practice purposeful and allow you to measure growth. They also give you excuses to buy new beads, which is one of the honest pleasures of this craft.

Bead weaving and loom work reward curiosity and patience in equal measure. With a modest set of tools, a few reliable stitches, and a willingness to experiment, you can make pieces that are both beautiful and durable. The learning curve is steady, and the community is welcoming — dive in one row at a time and enjoy the rhythm of making.